Element 4.1: Discover Your Comparative Advantage

“Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing it is stupid.”

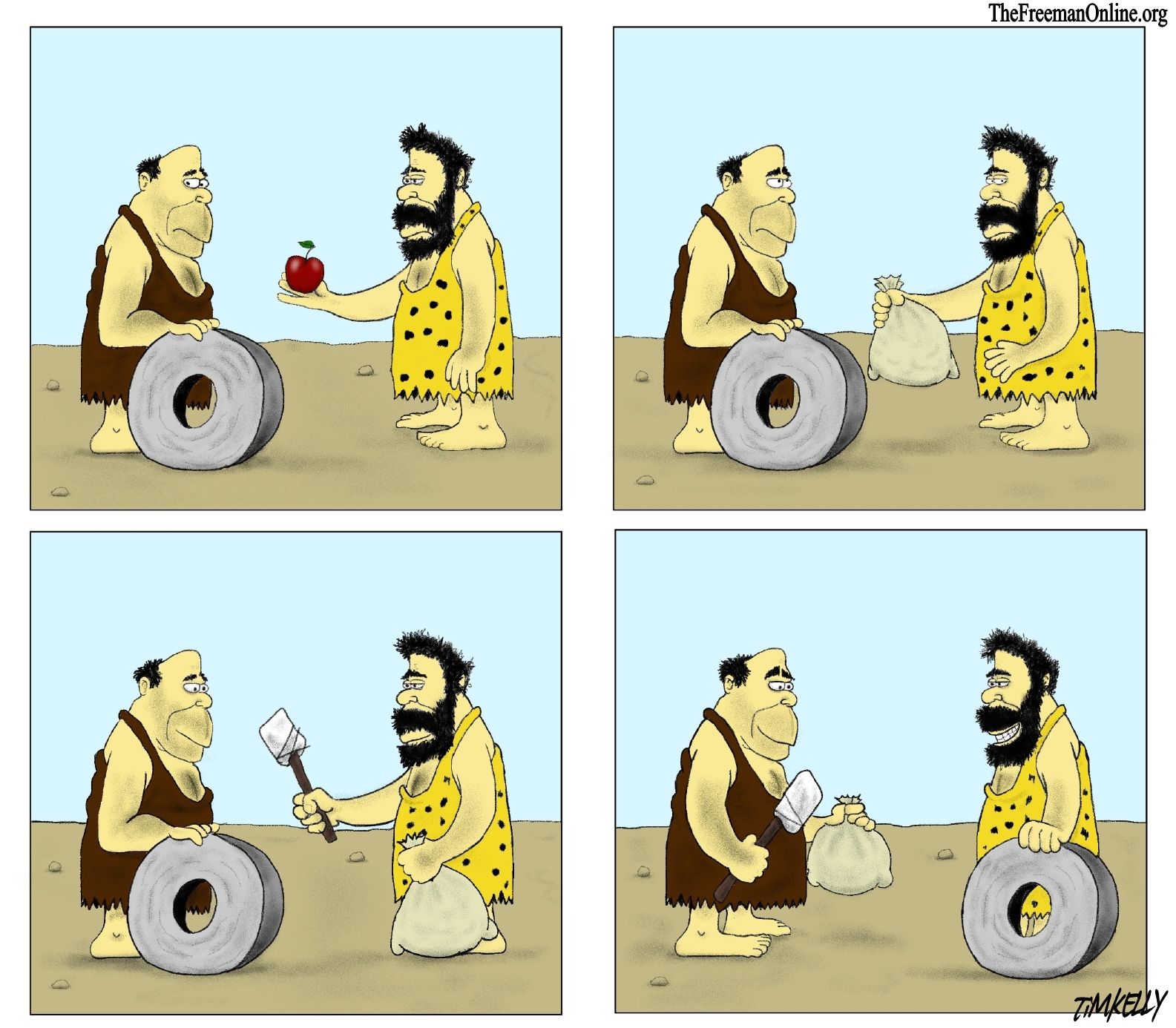

We have used the principle of comparative advantage throughout this book to explain the rationale for international trade and specialization across firms. The principle of comparative advantage is just as important when individuals are considering occupational and business opportunities. Think about the relationship between your skills and opportunity costs. To pick one extreme, suppose that someone is better than everyone else in every productive activity (i.e. they have an absolute advantage in everything). Should they try to meet all their needs and wants by spending a little time on each activity (and go to bed exhausted)? Now, let’s look at the other extreme: suppose someone is worse at everything than everyone else. Should they just give up and starve? The answer to both questions is “No!” In both circumstances each person would gain from specialization and trading with the other.

No matter how talented you are, when opportunity costs are considered, you will be relatively more productive in some areas than others. Similarly, no matter how poor your ability to produce, you will be able to make some things at a lower relative cost than other people. You will be able to compete successfully in some areas and can gain by specializing where you have a comparative advantage.

Your comparative advantage is determined by your relative abilities, not your absolute abilities. This point is very important. Instinctively you know this. Imagine your spouse is better than you are at both cooking and gardening. Marital harmony is unlikely if your spouse does all this work while you’re on social media all day. On the other hand, if you are even somewhat better at cooking than gardening and you trade your time and skills making delicious food for your spouse’s time and skills growing plants, you are both better off.

Some people start out with fewer advantages than others, but even they can do extremely well if they make the effort and apply themselves diligently. There is often great admiration for people who overcome difficult beginnings to become successful. Adversity—the determination to get out of a poor situation—can be a great motivator.

It’s never too early to take charge of your career development, to plan how you can best develop your talents and use market cooperation to achieve your goals. While you know your interests and skills, it will likely take information-gathering to shape them into goals. You may need to talk with the teachers who know you best, your parents and other relatives (from whom you will likely get the most risk-averse and conservative advice), and do some internet searches about the qualifications needed for a profession you might like to pursue. This blue-sky thinking costs almost nothing, and may lead you to consider professions you might not have thought of initially.

Three other helpful avenues to gain close-up experience about possible professions or professional environments are shadowing, volunteering and asking for informational interviews. Shadowing happens when you contact someone in a profession that interests you and ask if you can quietly be in the background with them for a day while they go about doing what they do. Don’t be afraid to contact someone you don’t know. Sometimes, people will just say, “no,” but a respectful email or letter of genuine interest may get a “yes.” It’s rather flattering to have a young person interested enough in what the established person does to want to make contact. It also shows a certain amount of risk taking and confidence in one’s interpersonal skills, qualities employers value. If fitting a day into your schedule doesn’t work, you can ask for a meeting to discuss this career. I have seen these person-to-person contacts be very successful for students in landing internships, future guidance and mentoring on education or career contacts, and in one case a good job (assistant to the president of the company!)

Volunteering in a field where people are marginalized and help is always needed, like working with the elderly or with people with disabilities, can be personally rewarding, and a way to try out career possibilities. An example: as 10th grade students Zara and Tina volunteered 3 hours a week after school at a hospital talking with and reading to chronically ill patients. While both found great satisfaction and new empathy for others, Zara decided that being a medical professional was not for her because she herself felt the pain of others too deeply. Tina, on the other hand, became a doctor.

Back to comparative advantage in making educational and career choices. We usually perceive costs as something that should be kept as low as possible. Remember, however, that costs reflect the highest valued opportunity given up when we choose an option. Thus, when you have attractive alternatives, your choices will be costly. Should you take that part-time job as a waiter or waitress to have more money while you’re a student? Or should you borrow money to take an extra course so that you can complete your college degree more quickly? Both options are attractive. Furthermore, as you improve your skills and your opportunities become even more attractive, the choice among options will be more costly.

In contrast, your costs will be low when you only have very few good choices. For example, a very effective way to reduce the cost of reading this book would be to get marooned with it on a desert island so that reading it was the only opportunity you had other than staring at the ocean. It would reduce the cost of doing one attractive thing, reading this book, by eliminating your opportunity to do many other attractive choices. While you might not have a choice about being marooned on a desert island, you do have choices to make yourself better off by increasing your opportunities, not by reducing them.

Young people are encouraged to pursue higher education so they will have more attractive opportunities later in life. But this is the same as encouraging them to increase the costs of all the choices they make. A good education will generally increase your productivity and the amount employers are willing to pay you. Although it will enhance your future earnings, it also means you will have to forego the three years of lower income you would have earned by going to work right out of high school.

Sound career decision-making involves more than figuring out the things you do best. It is also vitally important to discover where your passions lie—those productive activities that provide you with the most fulfillment. If you enjoy what you do and believe it is important, you will be happy to do more of it and work to do it better. Thus, competency and passion for an activity tend to go together and can be enhanced by your generosity to work for the greater good of your community (or all humankind if you’re really ambitious). Think about real wealth being measured in terms of personal fulfillment.