Element 3.8: Limit Welfare-Reducing Transfers

“I’ve been around long enough to establish that there are two things that, once people have them, they don’t want to give up…. One is privileges and the other is subsidies.”

To non-economists, income transfers look like an effective way to help targeted beneficiaries. Economic logic, however, indicates that transferring income to a group of recipients to improve their long-term well-being is very difficult. As is often the case in economics, the unintended secondary effects explain why this is so.(104)

Three major factors undermine the effectiveness of income transfers. While the process may be most vivid in the case of direct income transfers like welfare assistance, the same types of forces occur when the benefits are in-kind transfer such as India’s Food Distribution System, which provides billions of dollars in free or low-cost staple foods to low income families every year. Indeed, subsidies for production such as agricultural subsidies or grants to corporations raise similar issues.

First, an increase in government transfers will generally reduce the incentive to earn of both the taxpayer-donor and the transfer recipient. Under many transfer programs, as the recipient’s income rises, the magnitude of the transfer is reduced, because the recipient is now technically better off. As the poor work harder or get better jobs, it often generates taxes, that are, in fact, higher than those on more well-off citizens, therefore resulting in a loss of income. Recipients, therefore, have less incentive to earn because additional earnings will increase their net incomes by only a fraction—and in many cases only a small fraction—of the additional earnings. Similarly, as taxes increase to finance additional transfers, all taxpayers have less incentive to make the sacrifices needed to produce and earn and have more incentive to invest in “tax shelters” to try to hang on to their money. Thus, neither transfer recipients nor taxpayers in general will produce and earn as much as they would in the absence of the transfer programs. As a result, economic growth will be slowed.

To see the negative effect of almost any transfer policy on productive effort, consider the reaction of students if a professor announces at the beginning of term that the grading policy will be to redistribute the points earned on the exams so that no one will receive less than a C. Under this plan, students who earned As on exams by performing at the top of the class would have to give up enough of their points to bring up the average of those who would otherwise get Ds and Fs. Of course, the B students would also have to contribute some of their points as well, although not as many as A students, to achieve a more equal grade distribution.

Does anyone doubt that at least some of the students who would have made As and Bs will study less when their extra effort is “taxed” to provide benefits to others? Moreover, would the students who would have made Cs and Ds study less, since the penalty they pay for less effort would be cushioned by point transfers they would lose if they earned more points on their own. The same logic applies even to those who would have made Fs, although they probably weren’t doing very much studying anyway. Predictably, the outcome will be less studying, and overall achievement will decline.

The impact of tax-transfer schemes will be similar: less work effort and lower overall income levels. Income does not just happen -- it is something that people produce and earn. Individuals earn income as they provide goods and services to others willing to pay for them. We can think of national income as an economic pie, but it is a pie whose size is determined by the actions of millions of people, each using production and trade to earn an individual slice. It is impossible to redistribute income without simultaneously reducing the work effort and innovative actions that generate the income.

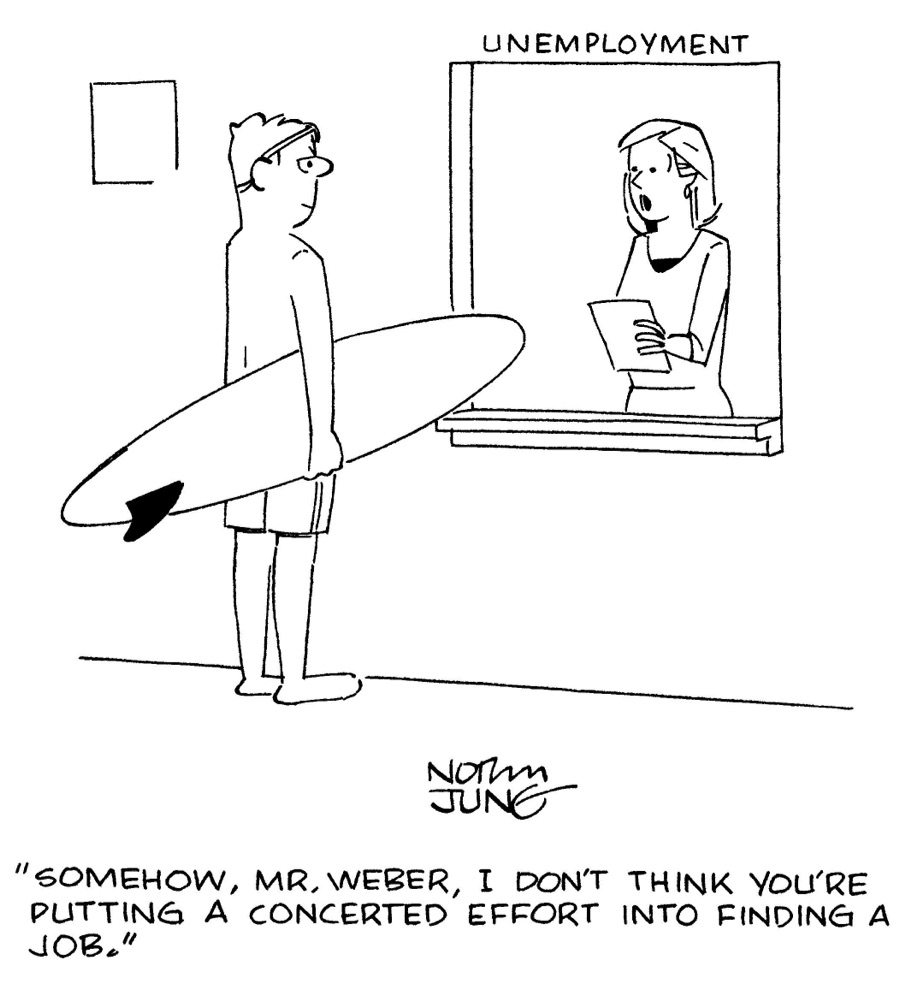

Second, competition for transfers will erode most of the long-term gains for the intended beneficiaries. Governments must establish a criterion for the receipt of income transfers and other political favors. If they do not, the transfers will bust the budget immediately. Generally, the government will require a transfer recipient to own something, do something, or be something. Two examples: the recipient of unemployment compensation must be out of a job; to qualify for a small-business grant or loan a company must have a limited number of employees. Once the criterion is established, many people will modify their behavior to qualify for the “free” money or other government favors. As they do so, and hire fewer workers or work less in order to qualify for the transfer their net gain from the transfers declines. In effect, the phase out rules for transfers as income rises actually imposes a very high tax rate on work, strongly reducing the incentive to take such work and often resulting in the recipient not gaining much labor market experiences and reducing their chances of getting better job offers in the future.

Think about the following: suppose that the German government decided to give away a €100 bill between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. each weekday to all persons willing to wait in line at the teller windows of the Ministry of Finance. Long lines would emerge. How long? How much time would people be willing to take from their leisure and their productive activities to wait in line? A person whose time was worth €15 per hour would be willing to spend about six hours waiting for the €100 bill. Others whose time was worth less, say €10, €8, or €5 per hour would wait longer—ten hours or more. And everyone would find that the time waiting consumed much of the value of the €100 transfer. If the proponents thought the program would make the recipients €100 better off, they would have been wrong.

This example illustrates why the intended beneficiaries of transfer programs are not helped as much as most supporters of such programs perceive. When beneficiaries must do something (for example, wait in line, fill out forms, lobby government officials, take an exam, endure delays, or contribute to selected political campaigns) to qualify for a transfer, much of their potential gain will be lost as they seek to meet the qualifying criteria. Similarly, when beneficiaries must own something (for example, land with a wheat production history to gain access to wheat program subsidies, or a license to operate a taxicab to get a subsidy), people will bid up the price of the asset needed to acquire the subsidy. The higher price of the asset, such as the taxicab license or the land with a history of wheat production, will capture the value of the subsidy.

In each case the potential beneficiaries will compete to meet the criteria until they dissipate much of the value of the transfer. As a result, the recipient’s net gain will generally be substantially less than the amount of the transfer payment. Indeed, the net gain of the marginal recipient (the person who barely finds it worthwhile to qualify for the transfer) will be very close, if not equal, to zero.

Consider the impact of the subsidies (grants and low-cost loans) to college students in the United States. These programs were designed to make college more affordable, but the subsidies increase the demand for college, which pushes tuition prices upward. About 60 percent of the increase in transfers to students was passed through in the form of higher tuition prices according to a 2017 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Put another way, for every $3 increase in student subsidies, colleges and universities raised tuition by almost $2.(105) It is no coincidence that as the grant and loan aid programs for college students have increased substantially since 1990, tuition and other expenses of college have increased far more rapidly than the general level of prices.(106) Furthermore, the subsidy programs have contributed to a glut of college students entering the job market, which has reduced their employment prospects as well as their future earnings, making it harder to pay back their loans. When the secondary effects—higher college costs and less attractive employment opportunities—are taken into consideration, the net benefits to college students may be substantially less than the transfers. In post-communist transition countries, rapid expansion, combined with low quality and irrelevance (in many fields) of university education, has resulted in a serious problem of “overeducation” where graduates end up taking jobs in which they do not need a university education. Many such graduates remain trapped in low-skilled jobs years after completing schooling.(107)

Transfer programs can even leave intended beneficiaries worse off. The US Homestead Act of 1862 illustrates this point. Under this legislation, the federal government provided a land plot of about 65 hectares, which later expanded to up to 240 hectares in parts of the West, to settlers who staked a claim, built a house on the land, and stayed for five years. This option attracted many, but it was not easy to survive in the early West, even with 65 hectares. Thus, more than 60 percent of the land claims were abandoned before the five years elapsed.(108) In essence, this transfer program encouraged people to settle the land before it was economical to do so, and as a result, many of the homesteaders suffered severe financial losses.

In today’s world, the issue of incentives generated by subsidies can be starkly seen when examining the problem of homelessness. In New York City, for example, the vast majority of homeless individuals are sleeping in a city-run or private shelter, not on the street. Many may have real mental or addiction problems, but many are also simply responding to incentives. If you are not currently homeless the wait time for receiving government low-cost housing in New York is more than 15 years, but if you are homeless, it is just a few months. Can you spot the incentive here? It may be optimal for someone who is not getting along with their parents to move to a shelter and become ‘homeless” in order to jump to the head of the queue for housing benefits. The possible negative secondary effect can only be imagined. Once again, we see the fundamental insight of economics, “Incentives Matter!”

Similarly, but perhaps less dramatically, as discussed in Part 2, Element 2.4, US government regulations designed to make home ownership more affordable encouraged lenders to extend loans to homebuyers with little or no down payment who could not qualify for conventional mortgages. The impact of these regulatory subsidies was much like those of the Homestead Act: high default rates, foreclosures, and financial troubles for many of the intended beneficiaries.

The third reason for the ineffectiveness of transfers is that transfer programs reduce the adverse consequences suffered by those who make imprudent decisions, reducing their motivation to avoid adversity. For example, government subsidies of insurance premiums in hurricane-prone areas reduce the personal cost to individuals protecting themselves against losses. There is a cost to society, however. Because the subsidy makes the purchase of hurricane insurance cheaper, more people will build in hurricane-prone areas than would be true if they had to pay the full cost. As a result, repairing the damage from hurricanes is greater than would otherwise be the case.

The impact of unemployment compensation is similar. The benefits make it less costly for unemployed workers to refuse existing offers and, instead, keep looking for better jobs. Therefore, workers engage in more lengthy job searches, pushing the unemployment rate upward.(109) When the War on Poverty was declared in the United States in the mid-1960s, President Lyndon Johnson and other proponents of the program argued that poverty could be eliminated if only Americans were willing to transfer a little more income to the less fortunate members of society. They were willing, and income-transfer programs expanded substantially. Measured as a proportion of total income, transfers directed toward the poor or near-poor (for example, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, food stamps, and Medicaid) doubled during the 1965–1975 period. Since 1975, anti-poverty income transfers have continued to grow as a share of national income.

No doubt, the proponents of the War on Poverty programs were motivated by lofty objectives. As we have stressed, however, good intentions do not guarantee the desired outcome. As Exhibit 24 shows, the poverty rate was declining rapidly prior to the War on Poverty. The share of families in poverty declined from 32 percent in 1947 to 13.9 percent in 1965. The downward trend continued for a few more years, reaching 10.1 percent in 1970. In the late 1960s, only a few years after the War on Poverty transfers were initiated, the declining trend in the poverty rate came to a halt. Since 1970, the poverty rate of families has fluctuated within a relatively narrow range between 8 percent and 12 percent. The poverty rate was 11.8 percent in 2010, and by 2020, just before the pandemic, it declined to approximately 9 percent. These rates are only slightly lower than the figure when the War on Poverty programs were initiated. Given that the 2020 income per person, adjusted for inflation, was two-and-a-half times the level of the late 1960s, this lack of progress in reducing poverty is startling.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, 1960 to 2022 (CPS ASEC).

The calculation of the official poverty rate does not include noncash benefits such as those of food, health care, and housing. If noncash benefits were counted as income, the family poverty rate would be about 3 percentage points lower, but the pattern is still the same as that in Exhibit 24. When noncash benefits are counted as income, the family poverty rate in 2015 is still almost the same as in 1970.

Why haven’t the anti-poverty transfer programs been more effective? The transfers generate three unintended secondary effects that slow progress against poverty.

Video:

First, the income-linked transfers reduce the incentive of low-income individuals to earn, move up the income ladder, and escape poverty. There are more than 75 means-tested government programs in the United States (for example, food supplements, Medicaid, housing subsidies, school lunches, and child health-care insurance) that target the poor for assistance. Benefits from most of these programs are scaled down and eventually eliminated as the recipients’ earnings rise. As a result, many low-income recipients get caught in a poverty trap. If they earn more, the combination of the additional taxes owed and transfers lost means that they get to keep only 10, 20, or 30 percent of the additional earnings. In some cases, the additional earnings may even reduce the recipient’s net income. This poverty trap reduces the incentive for many low-income recipients to work, earn more, acquire experience, and move up the job ladder. In 2018, the OECD reported that lost benefits as a result of increased earnings equaled 93 percent of the minimum wage for workers in the Czech Republic and 92 percent of this wage in Croatia.(110) In some cases, the additional earnings may even reduce the recipient’s net income. Thus, the poverty trap substantially reduces the incentive for many low-income recipients to work, earn more, acquire experience, and move up the job ladder. To a large degree, the transfers merely replace income that would have otherwise been earned, and as a result, the net gains of the poor are small—far less than the transfer spending suggests.

This insight is not a new. Observing the English Poor Laws in 1835, French political philosopher and economist, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Memoirs on Pauperism:

“Man, like all socially-organized beings, has a natural passion for idleness. There are, however, two incentives to work: the need to live and the desire to improve conditions of life… Any measure which establishes legal charity on a permanent basis and gives it an administrative form thereby creates an idle and lazy class, living at the expense of the industrial and working class.”(111)

Second, transfer programs that significantly reduce the hardship of poverty also reduce the opportunity cost of risky choices. Dropping out of school or the workforce, childbearing by teenagers and unmarried women, divorce, abandonment of children by fathers, and drug use often lead to poverty. As more people choose these high-risk options, it is very difficult to reduce the poverty rate. The poverty rate of single-parent households is substantially greater than that of two-parent households. In the Czech Republic, for example, 9.7 percent of the general population lived below the poverty line in 2017, while 37 percent of people in households with single mothers or fathers fell below this line. In Belarus in 2013 the poverty rate among single-parent households was 17 percent as compared to 11 percent for the general population. Isabel Sawhill and Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution found evidence that a person can reduce the chances of living in poverty from 12 percent to 2 percent by doing just three basic things: completing high school (at a minimum), working full-time, and getting married before having a child.(112) When young people choose these options, it is unlikely that they will spend any significant time in poverty. This is a vitally important point that educators, parents, guardians, and others need to discuss with young people, many of whom are making these life-changing decisions.

Third, government anti-poverty transfers crowd out private charitable efforts. When people perceive that the government is providing for the poor, action by families, churches, and civic organizations becomes less urgent. When taxes are levied and the government does more, predictably, private individuals and groups will do less. Yet private givers have real advantages over government transfers. They are typically local, therefore seeing the real nature of the problems more clearly, are often more sensitive to recipients’ lifestyles, and typically focus their giving on those making a good effort to help themselves.

In the words of Spencer Cox, governor of the State of Utah:

“We don’t need bigger government. We need bigger people. This is the model for a high-functioning society. It requires our best people to be regularly involved with our most challenged communities. From the doctor teaching literacy at an elementary school to the college student enrolled in weekly service at the food bank, the health of a society is determined by the internal forces in that community.”

From an economic viewpoint, the poor record of transfer programs, ranging from farm price supports to anti-poverty programs, is not surprising. When the secondary effects are considered, economic analysis indicates that it is extremely difficult to help the intended beneficiaries over the long term.

Read:

Social Cooperation and the Marketplace by Dwight Lee