Element 2.4: Efficient Capital Markets

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it is about the future.”

While consumption is the goal of all production, providing consumer goods may require using resources to build machines, heavy equipment, and buildings, that are then used to produce the desired consumer goods. Productive investment increases future consumption. Thus, capital investment—the construction and development of long-lasting resources designed to help produce more in the future—is an important source of economic growth. For example, the purchase of an oven by a local pizzeria will help enlarge its future output. Similarly, the purchase of additional trucks helps firms in the transport and logistics sector deliver more goods more rapidly.

Although the discussion below is in terms of physical goods, investment in developing skills or human capital is just as important and can be thought of in exactly the same way (most of the time) – the biggest difference is that while investors can own machines and even ideas (through a patent), they can only rent skills given that in civilized countries slavery is illegal!.

Resources (such as labor, land, and entrepreneurship) used to produce these investment goods will be unavailable to produce consumer goods. If we consume all that we produce, no resources are available for investment. Therefore, investment requires saving—a reduction in current consumption to make the funds available for alternative uses. Saving is an integral part of the investment process. Someone either the investor or someone willing to supply funds to the investor, must save to finance investment.

Not all investment activities, however, are productive. An investment will enhance the wealth of a nation only if the value of the additional output from the investment exceeds the cost. When it does not, the project is counterproductive and reduces wealth. Investments can never be made with perfect foresight, so even the most promising investment projects will sometimes fail to enhance wealth.

To make the most of its potential for economic progress, a nation must have mechanisms that attract savings and channel them into investments that create wealth. In a market economy, the capital market performs this function. The capital market, when defined broadly, includes the markets for stocks, bonds, and loans. These institutions channel funds from those who do not want to use these funds now (savers) to those who do not have sufficient funds to undertake a project they believe will be profitable (borrowers). Financial institutions such as stock exchanges, banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, and investment firms play important roles in the operation of the wealth-enhancing capital market.

Private investors, such as small business owners, corporate stockholders, and venture capitalists place their own funds at risk in the capital market. Investors will sometimes make mistakes and undertake projects that prove to be unprofitable. If investors were unwilling to take such chances, many new ideas would go untested and many worthwhile but risky projects would not be undertaken.

Consider the roles of entrepreneurship, risk-taking, and the capital market in the development of internet services. In the mid-1990s, Sergey Brin and Larry Page were graduate students at Stanford University, working on a research project designed to make finding things on the internet easier. They might have seemed unlikely candidates for entrepreneurial success. But in 1998, Brin and Page founded Google, a business that provides free internet services while generating revenues through advertising. Their powerful internet search engine increases the productivity of millions of individuals and businesses each second. Consequently, they have earned a fortune by making Google a household name and by employing about 180,000 full-time individuals worldwide in 2023. Many other internet-based companies, such as eBay, Alibaba, Zalando and Amazon, were similar entrepreneurial ventures that have become household names and also earned enormous profits.

But the experience of numerous other internet-based firms was quite different. Many so called “dot-coms,” like Pets.com, Boo.com, Webvan and eVineyard are no longer in business their revenues did not sufficiently cover costs soon enough for investors to continue to believe in their futures. The high hopes of these firms did not materialize. They failed.

In a world of uncertainty, mistaken investments are a necessary price that must be paid for fruitful innovations in new technologies and products. Such counterproductive projects, however, must be recognized and brought to a halt. In a market economy, the capital market performs this function. If a business continuously experiences losses, eventually investors will terminate the project, stop wasting their money, and turn elsewhere. Note that a key word in the previous sentence is “continuously.” One of the key functions of capital markets is to enable entrepreneurs with ideas that would ultimately be successful to survive long enough for their potential to be realized, which may take more time than almost anyone’s personal resources would allow. One of the market-defining innovations of recent years, Uber, “lost” billions of dollars of investors’ money before turning almost $2 billion in profit in 2023.

Given the pace of change and the diversity of entrepreneurial talent, the knowledge required for sound decision-making about the allocation of capital is far beyond the scope of any single individual. More important, it is beyond the ability of any government agency. Without a private capital market, there is no mechanism that can consistently channel investment funds into wealth-creating projects and out of counterproductive ones.

Why? When investment funds are allocated by the government, rather than by the market, an entirely different set of factors comes into play. Political influence rather than potential market returns determine which projects are undertaken. Investment projects that reduce rather than create wealth become far more likely.

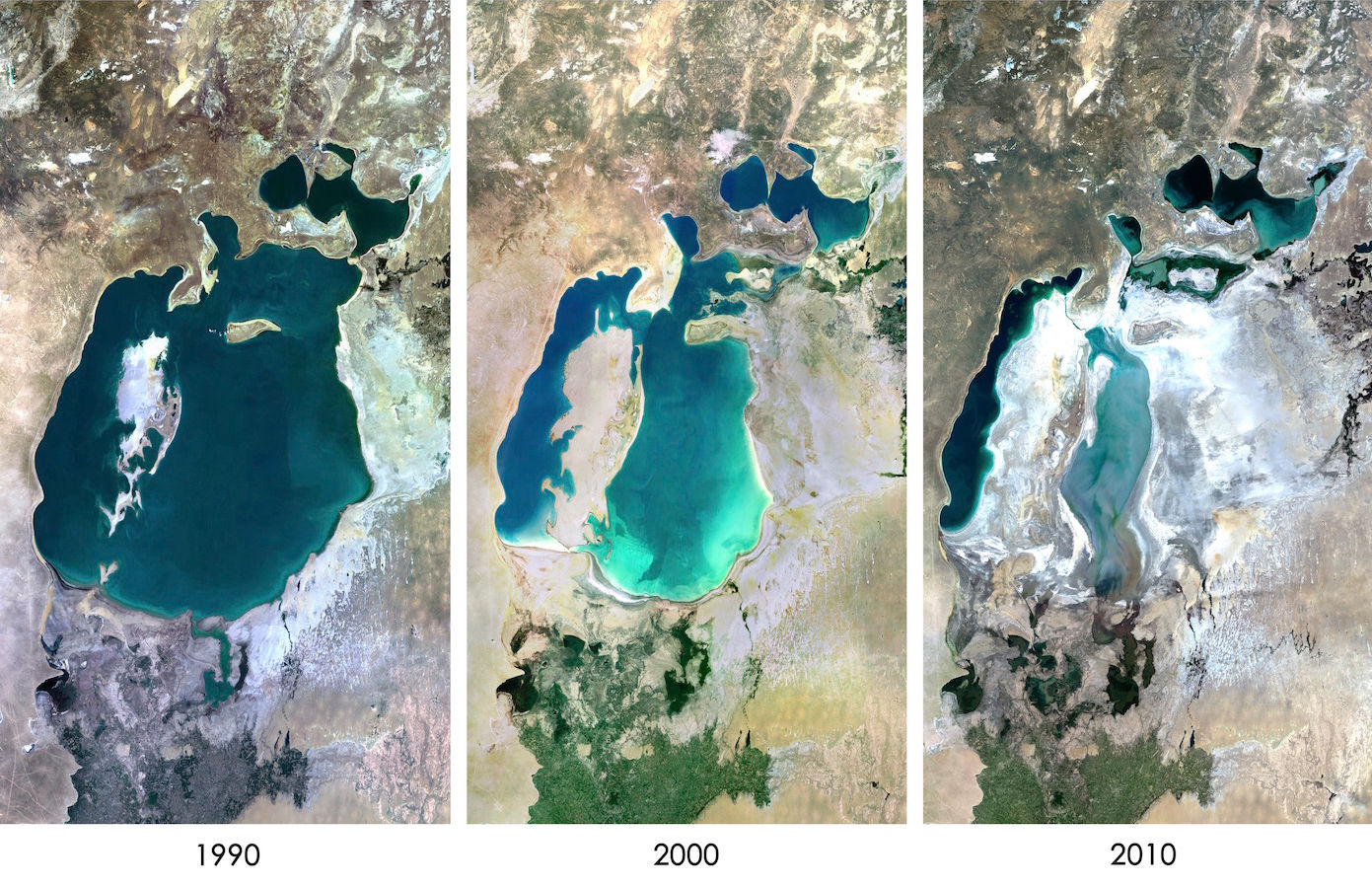

The experiences of the centrally planned socialist economies during the Soviet era illustrate this point. For four decades (1950–1990), the investment rates in these countries were among the highest in the world. Central planners channeled approximately one-third of the national output into capital investment. These high rates of investment, however, did little to improve living standards, because political rather than economic considerations determined which projects were funded. Resources were often wasted on projects with high costs or favored by leaders who wanted high-visibility, prestigious investments. Misdirection of investment and failure to keep up with dynamic change eventually led to the demise of socialism in most of the Soviet countries. Several examples illustrate this misallocation. In 1931 Stalin insisted on building the White Sea-Baltic Canal, but to meet his unreasonable schedule the canal was too shallow to be useful. Khrushchev’s campaign to make Kazakhstan produce wheat at the level of American and Canadian prairies and Uzbekistan cotton as profitably as the American south resulted in vast irrigation schemes, which eventually destroyed the Aral Sea.(52) The Siberian River Reversal Project stands out as another notable failure. Conceived by Soviet engineers, this ambitious plan aimed to redirect water from Siberia's vast rivers, like the Ob and Irtysh, to the dry areas of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. However, by the early 1980s, concerns over the potential environmental impact and questions about the project's economic feasibility, considering the massive construction and operational costs, led to its abandonment.

Of course, there is no clean distinction between planned and market economies. Even in the Soviet Union and Communist China there were small, residual, examples of private enterprise, Other countries such as Venezuela, Iran and Lybia are highly planned (and suffering because of it). In the years immediately following World War 2 even France and the United Kingdom adopted a heavily state-controlled economic model under the doctrine of dirigisme. Eventually, these were abandoned by voters as failures.

Video:

The U.S. experience with political allocation of capital is similar. The housing market illustrates this point. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) were chartered by Congress as government-sponsored corporations in 1938 and 1970, respectively. Because of their government backing, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could borrow funds at about half of a percentage point less than private firms. This gave them a huge advantage. By the mid-1990s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac held approximately 40 percent of all home mortgages. Moreover, during 1998–2008, these government-sponsored enterprises purchased more than 80 percent of the mortgages sold by banks and other mortgage originators.

As long as these institutions stuck to their original missions, things were fine. Government planners, however, could not let well enough alone. Beginning in the 1990s, Congress forced Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to engage in social policies, extending a larger and larger share of their loans to low-and middle-income borrowers who did not have adequate incomes or collateral to support a traditional mortgage. How did this political allocation of capital work out? To meet the congressional mandates, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loosened lending standards. They began extending loans with little or no down payment, lending funds to borrowers with poor credit records, and permitting people to borrow larger amounts relative to their income and the price of the house purchased.

As the mortgage lending standards eroded and loose credit became more readily available, the initial effects seemed positive. The demand for housing increased, housing prices soared during 2001–2005, and the construction industry boomed. By mid-2006, however, housing prices leveled off and soon many who borrowed beyond their means stopped making payments. Mortgage defaults soared, foreclosures expanded, and the financial turmoil led to a severe recession in 2008–2009. By the summer of 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were insolvent, and the American taxpayer was left with approximately $400 billion of bad debt.

Although the specifics were different, the United States was not the only country where misguided government policies created a crisis in the housing market in the years just before 2010. Between 2007 and 2010 average house prices fell by approximately 35 percent in Ireland and by half or more in Dublin. Following the crash of the “Irish housing bubble,” evaluation by outside experts, including senior finance ministry officials from Canada and Finland, attributed the overheated market to a combination of excessively low interest rates set by the European Central Bank (ECB), massive increases in Irish government spending encouraged by higher than expected property tax revenue, and, especially, a government policy that attempted to encourage home ownership by allowing mortgages for 100 percent of a home’s purchase price, just like in the United States. Corruption also played a role.(53) Similar policies in Spain created precisely the same result during the same time frame. Another example is Greek Debt Crisis which erupted in 2009, plunging Greece into the deepest economic crisis in its modern history. It was part of the wider European sovereign debt crisis. For years, Greek government policies were characterized by high levels of public spending, generous pension schemes, and extensive public sector employment, which were not sustainable without significant reforms or sources of revenue. The Greek Debt Crisis serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of fiscal mismanagement.

One issue that has always been important but is becoming increasingly so in the modern world is that capital is highly mobile across national boundaries. Government intervention or poor supervision in one country will have spillover effects worldwide. Not only will economic crises reverberate, but, more critically, investors and entrepreneurs in countries where planners limit their opportunities will flee to those who are more welcoming.

When governments are heavily involved, allocation of investment is inevitably characterized by favoritism, conflict of interest, inappropriate financial relations, and various forms of corruption. When actions of this type occur in other countries, they are often referred to as crony capitalism. Historically, the government has played a larger role in the allocation of investment in other countries than in the United States, but the American experience with government allocation of investment funds for housing illustrates that crony capitalism occurs in the United States as well. Regardless of the label, political allocation of capital imposes a heavy cost on citizens.