Element 1.2: All choices involve costs

“There are no solutions, only tradeoffs.”

The reality of life on our planet is that productive resources are limited, while human desire for goods and services is virtually unlimited. Would you like to have some new clothes, a luxury boat, or a new smartphone? How about more time for leisure, recreation, and travel? Do you dream of driving your brand-new electric sports car into the driveway of your home? Most of us would like to have all of these things and many others! However, we are constrained by the scarcity of resources, including a limited availability of time.

In the late nineteenth century, many taverns offered a “free lunch” to anyone who bought a drink. Of course, since you had to buy a drink, the lunch wasn’t actually free—in addition (the story goes), the lunch had salty foods like ham, cheese, and peanuts, causing customers to buy more drinks. Thus, they paid in full for their “free lunches.”

This led to a phrase popular among economists: “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” The phrase was popularized in economics by the famous economist, Milton Friedman, who used it as the title of a book in 1975. An example of free lunch thinking could be a system of subsidized housing. During the Soviet era, housing was often provided "free" by the state. This, however, wasn't actually without cost. The apparently "free" housing was paid for indirectly by citizens through other means, such as long working hours, low wages, and the lack of choice or freedom to live where they wished. We cannot have as much of everything as we would like. So we choose among alternatives. (In the example of Soviet housing the consumer did not even make a choice – it was made for her by the state!) The choice to do one thing requires sacrificing the opportunity to do something else. This is why all costs are opportunity costs, and all choices involve forgoing other opportunities.

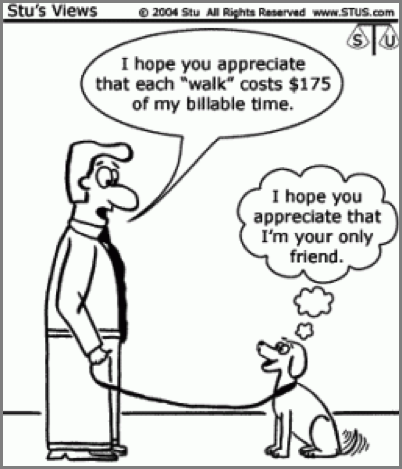

Many costs are measured in terms of money, where the trade-off is easy to see. The money you spend one way is not available to spend in other ways or for savings. The opportunity cost of your purchase reflects the value you place on the options you have given up because of your initial purchase. Even when you don’t have to spend money to do something, however, the action is not costless. You don’t spend money to take a walk and enjoy a beautiful sunset, but there is an opportunity cost to taking the walk. The time you spend walking could be used to do something else you value, like visiting a friend, working out, or reading.

Video:

Everyone has heard people claim that some things are so important that costs do not matter. Making such a statement may sound reasonable at first and may be an effective way to encourage other people to spend more money on things that we value (and for which we would like others to help pay). But the unreasonableness of ignoring cost becomes obvious once the costs of the forgone alternatives are considered. Saying that something should be done without considering the costs is really saying that we should do it without considering the value of the alternatives. When we choose between mutually exclusive alternatives, the one that costs least relative to the benefits it yields is the most valuable one.

The choices of both consumers and producers involve costs. As consumers, the cost of a good, as reflected in its price, helps us compare our desire for a product against our desire for alternative products. If we do not consider the costs, we will probably end up using our income to purchase the “wrong” things. You know—Buyer’s remorse—you bought something without seriously considering the more valuable alternatives.

Producers face costs, too—the costs of the resources used to make a product or to provide a service. For example, using resources such as labor, lumber, steel, and sheetrock to build new houses takes resources away from the production of other goods, such as hospitals and schools. High costs signal that the resources have other highly valued uses, as judged by buyers and sellers in other markets. Profit-seeking firms will heed those signals and act accordingly, such as seeking out less costly substitutes.

Government policies can distort and override these signals; they can introduce taxes or subsidies that help those interest groups inconvenienced by the competitive prices that emerge in free and open markets. But such policies reduce the ability of market incentives to guide resources to where consumers ultimately, on balance, value them most highly.

A classic example occurred in the country of Georgia between 1991 and 1994. The government froze bread prices at a below market level, resulting in consumers standing in queues that could stretch for more than a kilometer. The day price controls were removed, shops were all of a sudden well stocked and there were no queues! A similar phenomenon also from Georgia occurred in the winter of 2006 when a pipeline delivering gas from Russia exploded, resulting in a huge increase in demand of kerosene to provide heat. To prevent price gouging, controls were imposed on kerosene, again resulting in long lines until prices were freed and allowed to rise to the market-clearing level.

Politicians, government officials, and lobbyists often speak of “free education,” “free medical care,” or “free housing.” This terminology is deceptive. These things are not free. Production of each requires the use of scarce resources that could have been used to produce other things. For example, the buildings, labor, and other resources used to produce schooling could have been used to produce more food or recreation, protect the environment, or provide health care. The cost of the schooling is the value of those goods that must be sacrificed. Governments may be able to shift costs, but they cannot eliminate them.

Opportunity cost is an important concept. Everything in life is about opportunity cost. Everyone lives in a world of scarcity and, therefore, must make choices. By looking at opportunity costs, we can better understand the world in which we live. Let us consider the impact of opportunity cost on workforce participation, the birth rate, and population growth, topics many would consider outside the realm of opportunity-cost application.

Have you ever thought about why women with more education are more likely to work outside the home than their less-educated counterparts? Opportunity cost provides the answer. The more highly educated women will have better earning opportunities in the workforce, and therefore, it will be more costly for them to stay at home. The data are consistent with this view.

In 2022, in Georgia, about 53% of women in labor force with higher education were employed. This contrasted with a 39% employment rate for those with vocational education and roughly 25% for those with only upper secondary education. At the lower end of the spectrum, only about 10% of women with primary or lower secondary education were employed. These figures align with economic predictions that the greater the potential loss of income — or opportunity cost — from not working, the more likely women are to seek employment. Just as economic theory predicts, when it is more costly for a woman not to work outside the home, fewer will choose this option.(4)

Source: National Statistics Office of Georgia. www.geostat.ge

What do you think happens to the birth rate as an economy grows and earnings rise? Time spent on household responsibilities reduces the time available for market work. As earnings rise, the opportunity cost of having children and raising a large family increases. Therefore, the predicted result is a reduction in the birth rate and slower population growth. During the past two centuries, as the per capita income of a country increased, a reduction in the birth rate and a slowdown in population growth soon followed. Moreover, this pattern has occurred in every country. Even though there are widespread cultural, religious, ethnic, and political differences among countries, the higher opportunity cost of having children exerted the same impact on the birth rate in all cases. Over the past six decades, the global fertility rate has halved, dropping from an average of 4.6 births per woman in 1961 to 2.3 in 2021. This decline in births per woman has varied by country. In Armenia, the fertility rate fell from 4.7 to 1.6, while Azerbaijan saw a decrease from 5.9 to 1.5. Georgia experienced a decline from 2.9 to 2.1, and Ukraine's fertility rate dropped from 2.2 to 1.2 during the same period, according to the World Bank data.

Opportunity cost is a powerful tool. It will be applied again and again throughout this book. If you integrate this tool into your thought process, it will greatly enhance your ability to understand the real-world behavior of consumers, producers, business owners, political figures, and other decision-makers. Even more important, the concept will also help you make better personal choices.