| ≡AAAAAAA | Common Sense Economics | ← → |

Imprint

COMMON SENSE ECONOMICS

What Everyone Should Know About Personal and National Prosperity

What Everyone Should Know About Personal and National Prosperity

Revised for Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union

JAMES D. GWARTNEY

Florida State University

Florida State University

RICHARD L. STROUP

North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University

DWIGHT R. LEE

Southern Methodist University

Southern Methodist University

TAWNI H. FERRARINI

Northern Michigan University

Northern Michigan University

JOSEPH P. CALHOUN

Florida State University

Florida State University

RANDALL K. FILER

Hunter College & the CUNY Graduate Center

Hunter College & the CUNY Graduate Center

“Common Sense Economics: What Everyone Should Know About Personal and National Prosperity” by James D. Gwartney, Richard L. Stroup, Dwight R. Lee, Tawni H. Ferrarini, Joseph P. Calhoun and Randall K. Filer.

First published 2020.

Economic Fundamentals Initiative, 110 Jabez Street 1060, Newark, New Jersey NJ 07105, USA.

Revised for Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union from the third edition of “Common Sense Economics: What Everyone Should Know About Wealth and Prosperity” by James D. Gwartney, Richard L. Stroup, Dwight R. Lee, Tawni H. Ferrarini and Joseph P. Calhoun.

Copyright © Economic Fundamentals Initiative

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The text of the license is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

ISBN 978-1-952729-00-3

Preface

The authors of this book want you to live a successful and fulfilling life. We also want you, and every other individual, to live in an environment that allows and encourages everyone to reach their maximum potential. We believe that accomplishing these goals requires both leaders and citizens in general to understand the basic principles of economics. Economic decisions and policies affect each of us in almost every aspect of our daily lives, often in ways we do not fully comprehend. We are continually amazed by the degree of economic illiteracy among politicians and voters. Bad economics is dangerous everywhere, but is especially common, and harmful, in developing and post-communist transition economies. The fundamental purpose of the Common Sense Economics project is to make the key understandings of our profession accessible to all.

Because time is valuable, we have crafted this publication in a way that minimizes the requirement to learn new terms, memorize formulas, or master intricate details important only to professional economists. Rather, we focus on the fundamental insights of economics that really matter—those that will help you make better choices, improve your understanding of our increasingly complex world, and live a more satisfying life.

Regardless of your current knowledge of economics, this book will provide you with important insights. We have tried to make it concise, thoughtfully organized, and reader-friendly. As the work’s title suggests, we believe that the basic principles of economics primarily reflect common sense. The work puts these principles to work, demonstrating their power to explain real world events.

We aim to help you understand why some nations prosper and others do not. The political process is examined and differences between government and market allocation investigated. Even advanced students of economics and business will benefit from our efforts to pull together the “big picture.” You can temporarily set aside the complex formulas, sophisticated models, and technical mathematics of the profession and concentrate on the economic principles that attracted you to economics in the first place.

The materials are designed to provide a strong foundation, especially for students who may not take another economics course as well as for the general public who want an insight into the workings of the world around them. It is written to be appropriate for secondary school students, for university students in fields other than economics (such as law or journalism), and, especially, for all citizens.

Because the Common Sense Economics team is anxious to share these materials with instructors, we can offer workshops designed to enhance the ability of instructors to make the best possible use of our materials. If you would like more information on these activities, please consult our website at http://www.econfun.org.

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, many are questioning the pace and direction of the transition. It is especially important that citizens of the region are not sucked in by the false promises of “illiberal democracy” or “state capitalism.” Many individuals sacrificed their time, their careers, and even their lives to secure the blessings of political and economic freedom to this region. We dedicate this book to those heroes of liberty.

Part 1: Twelve Key Elements of Economics

The Twelve Key Elements

- Incentives matter: Changes in benefits and costs will influence choices in a predictable manner.

- There is no such thing as a free lunch: Goods are scarce and therefore we have to make choices.

- Decisions are made at the margin: If we want to get the most out of our resources, options should be chosen only when the marginal benefits exceed the marginal cost.

- Trade promotes economic progress.

- Transaction costs are an obstacle to trade.

- Prices bring the choices of buyers and sellers into balance.

- Profits direct businesses toward productive activities that increase the value of resources, while losses direct them away from wasteful activities that reduce resource value.

- People earn income by providing others with things they value.

- High living standards result from the production of goods and services people value, not from just “having a job.”

- Economic progress comes primarily through trade, investment, better ways of doing things, and sound economic institutions.

- The “invisible hand” of market prices directs buyers and sellers toward activities that promote the general welfare.

- Too often long-term consequences, or the secondary effects, of an action are ignored.

Introduction

Life is about choices, and economics is about how incentives affect those choices and shape our lives. Choices about our education, how we spend and invest, what we do in the workplace, and many other personal decisions will influence our well-being and quality of life. Moreover, the choices we make as voters and citizens affect the laws or “rules of the game,” and these rules exert an enormous impact on our freedom and prosperity. To choose intelligently, both for ourselves and for society generally, we must understand some basic principles about how people choose, what motivates their actions, and how their actions influence their personal welfare and that of others. Thus, economics is about human decision-making, the analysis of the forces underlying choice, and the implications for how societies work.

The economic way of thinking involves the integration of key concepts into your thought process. The following section presents twelve concepts that are crucial for the understanding of economies, and why some countries grow and achieve high income levels while others stagnate and remain poor. You will learn such things as the true meaning of costs, why prices matter, how trade furthers prosperity, and why production of things that people value underpins our standard of living. In the subsequent parts of the book, these concepts will be used to address other vitally important topics.

Element 1.1: Incentives Matter

Changes in benefits and costs will influence choices in a predictable manner.

All of economics rests on one simple principle: Changes in incentives influence human behavior in predictable ways. Both monetary and nonmonetary factors influence incentives. If something becomes more costly, people will be less likely to choose it. Correspondingly, when the benefits derived from an option increase, people will be more likely to choose it. This simple idea, sometimes called the basic postulate of economics, is a powerful tool because it applies to almost everything that we do.

People will be less likely to choose an option as it becomes more costly. Think about the implications of this proposition. When late for an appointment, a person will be less likely to take time to stop and visit with a friend. Fewer people will go picnicking on a cold and rainy day. Higher prices will reduce the number of units sold. Attendance in college classes will be below normal the day before school holidays. In each case, the explanation is the same: As the option becomes more costly, less is chosen.

Similarly, when the payoff derived from a choice increases, people will be more likely to choose it. A person walking along the street will be more likely to bend over and pick up a Euro or a Dollar than a cent. Students will attend and pay more attention in class when they know the material will be on the exam. Customers will buy more from stores that offer low prices, high-quality service, and a convenient location. Employees will work harder and more efficiently when they are rewarded for doing so. All of these outcomes are highly predictable and they merely reflect the “incentives matter” postulate of economics.

This basic postulate explains how changes in market prices alter incentives in a manner that works to coordinate the actions of buyers and sellers. If buyers want to purchase more of an item than producers are willing (or able) to sell, its price will soon rise. As the price increases, sellers will be more willing to provide the item while buyers purchase less, until the higher price brings the amount demanded and the amount supplied into balance. At that point the price stabilizes.

What happens if it starts out the other way: if sellers want to supply more than buyers are willing to purchase? If sellers cannot sell all of their goods at the current price, they will have to cut the price of the item. In turn, the lower price will encourage people to buy more—but will also discourage producers from producing as much, since it is less attractive to them to supply the product at the new, lower price. Again, the price change works to bring the amount demanded by consumers into balance with the amount produced by suppliers. At that point there is no further pressure for a price change.(1)

For example, bad weather raised the prices of peaches in the U.S. state of Georgia in the summer of 2014, forcing a price increase of 180% compared to the previous year. Despite the huge increase in price, consumers did not complain. Why? When the higher prices made it more costly to purchase peaches, most consumers easily substituted other fruits for peaches, either totally or partially, and made their winter jam reserves from pears or quinces instead.

Furthermore, as buyers reacted to higher peach prices, so did sellers. The farmers supplying peaches planted new trees. Other farmers cut down their apple and pear orchards and planted peach trees instead. Eventually, after two years (when the newly planted trees became fruitful) the price of peaches fell as supply expanded.

Incentives also influence political choices. There is little reason to believe that a person making choices in the voting booth will behave much differently than when making choices in the shopping mall. In most cases voters are likely to support political candidates and policies that they believe will provide them with the most personal benefits, net of their costs. They will tend to oppose political options when the personal costs are high compared to the benefits they expect to receive. For example, senior citizens have voted numerous times against candidates and proposals that would reduce their pension benefits. Opposition to proposed reductions in pension benefits is widely blamed for the poor showing of the United Russia party in Russia’s September 2018 gubernatorial elections. Similarly, polls indicate that students are strongly supportive of educational grants to college students.

There’s no way to get around the importance of incentives. They are a part of human nature. Incentives matter just as much under socialism as they do under capitalism. In the former Soviet Union, managers and employees of glass plants were, at one time, rewarded according to the tons of sheet glass they produced. Because their revenues depended on the weight of the glass, most factories produced sheet glass so thick that you could hardly see through it. As a result, the rules were changed so that the managers were compensated according to the number of square meters of glass produced. Under these rules, Soviet firms made glass so thin that it broke easily. Similarly, when quotas for the number of shoes were set for Polish factories which were, in turn, provided with too little leather, is it any wonder that there was a glut of children’s shoes on the market?

Some people think that incentives matter only when people are greedy and selfish. This is untrue. People act for a variety of reasons, some selfish and some charitable. The choices of both the self-centered and altruistic will be influenced by changes in personal costs and benefits. For example, both the selfish and the altruistic will be more likely to attempt to rescue a child in a shallow swimming pool than in the rapid currents approaching Dettifoss waterfall.(2) And both are more likely to give a needy person their hand-me-downs rather than their best clothes.

Even though no one would have accused the late Albanian, Mother Teresa, of greediness, her self-interest caused her to respond to incentives, too. When Mother Teresa’s organization, the Missionaries of Charity, attempted to open a shelter for the homeless in New York City, the city required expensive alterations to its building. The organization abandoned the project. This decision did not reflect any change in Mother Teresa’s commitment to the poor. Instead, it reflected a change in incentives. When the cost of helping the poor in New York went up, Mother Teresa decided that her resources would do more good in other areas.(3) Changes in incentives influence everyone’s choices, regardless of the mix of greedy, materialistic goals on the one hand and compassionate, altruistic goals on the other, which are driving a specific decision.

Element 1.2: There Is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch

Goods are scarce and, therefore, we have to make choices.

The reality of life on our planet is that productive resources are limited, while the human desire for goods and services is virtually unlimited. Would you like to have some new clothes, a luxury boat, or a vacation in the Swiss Alps? How about more time for leisure, recreation, and travel? Do you dream of driving your brand-new Porsche into the driveway of your oceanfront house? Most of us would like to have all of these things and many others! However, we are constrained by the scarcity of resources, including a limited availability of time.

Because we cannot have as much of everything as we would like, we are forced to choose among alternatives. There is “no free lunch.” Doing one thing makes us sacrifice the opportunity to do something else we value. This is why economists refer to all costs as opportunity costs.

Many costs are measured in terms of money, but these too are opportunity costs. The money you spend on one purchase is money that is not available to spend on other things. The opportunity cost of your purchase is the value you place on the items that must now be given up because you spent the money on the initial purchase. But just because you don’t have to spend money to do something does not mean the action is costless. You don’t have to spend money to take a walk and enjoy a beautiful sunset, but there is an opportunity cost to taking the walk. The time you spend walking could have been used to do something else you value, like visiting a friend or reading a book.

It is often said that some things are so important that we should do them without considering the cost. Making such a statement may sound reasonable at first thought, and may be an effective way to encourage people to spend more money on things that we value and for which we would like them to help pay. But the unreasonableness of ignoring cost becomes obvious once we recognize that costs are the value of forgone alternatives (that is, alternatives given up). Saying that we should do something without considering the cost is really saying that we should do it without considering the value of the alternatives. When we choose between mutually exclusive (but equally attractive) alternatives, the least-cost alternative is the best choice.

The choices of both consumers and producers involve costs. As consumers, the cost of a good, as reflected in its price, helps us to compare our desire for a product against our desire for alternative products that we could purchase instead. If we do not consider the costs, we will probably end up using our income to purchase the “wrong” things—those goods and services not valued as much as the other items we might have bought.

Producers face costs, too—the costs of the resources used to make a product or provide a service. For example, the use of resources such as lumber, steel, and sheet rock to build a new house takes resources away from the production of other goods, such as hospitals and schools. High costs for resources signal that the resources have other highly valued uses, as judged by buyers and sellers in other markets. Profit-seeking firms will heed those signals and act accordingly, such as seeking out less costly substitutes. However, government policies can override these signals. They can introduce taxes or subsidies to gain favor with potential supporters by lowering the prices that emerge in free and open markets. But such policies reduce the ability of market incentives to guide resources to where consumers ultimately, on balance, value them most highly. A classic example occurred in Georgia between 1991 and 1994. The government froze bread prices at a below market level, resulting in consumers standing in queues that could stretch for more than a kilometer. The day price controls were removed, shops were all of a sudden well stocked and there were no queues! A similar phenomenon also from Georgia occurred in 2006 when a pipeline delivering gas from Russia exploded, resulting in a huge increase in demand for heating kerosene. To prevent “price gouging,” controls were imposed on kerosene, again resulting in long lines until prices were freed and allowed to rise to the market-clearing level.

Politicians, government officials, and lobbyists often speak of “free education,” “free medical care,” or “free housing.” This terminology is deceptive. These things are not free. Scarce resources are required to produce each of them and alternative uses exist. For example, the buildings, labor, and other resources used to produce schooling could instead produce more food, recreation, environmental protection, or medical care. The cost of the schooling is the value of those goods that must be sacrificed. Governments may be able to shift costs, but they cannot eliminate them. When governments want to encourage people to save for their retirement, a massive advertising program typically proves ineffective, but a tax-deferred savings account often works.

Opportunity cost is an important concept. Everything in life is about opportunity cost. Everyone lives in a world of scarcity and therefore must make choices. By looking at opportunity costs, we can better understand the world in which we live. Consider the impact of opportunity cost on workforce participation, the birth rate, and population growth—topics many would consider outside the realm of opportunity-cost application.

Have you ever thought about why women with more education are more likely to work outside the home than their less educated counterparts? Opportunity cost provides the answer. The more highly educated women will have better earning opportunities in the workforce, and therefore it will be more costly for them to stay at home. The data are consistent with this view. In 2014, in Ukraine, more than 70% of women in the labor force aged fifteen to sixty-four with a second stage of tertiary education were employed, compared to 62% of their counterparts with only incomplete tertiary education and 40% of the women with upper secondary schooling.(4) Just as economic theory predicts, when it is more costly for a woman not to work outside the home, fewer will choose this option.

Exhibit 1: Employment-to-Population Ratio by Gender (Population Aged 15–64) in Ukraine, in percent

Source: Labor Force Survey 2014.

What do you think happens to the birth rate as an economy grows and earnings rise? Time spent on household responsibilities reduces the time available for market work. As earnings rise, the opportunity cost of having children and raising a large family increases. Therefore, the predicted result is a reduction in the birth rate and slower population growth. The real world reflects this analysis. During the past two centuries, as the per capita income of a country increased, a reduction in the birth rate and a slowdown in population growth soon followed. Moreover, this pattern has occurred in every country. Even though there are widespread cultural, religious, ethnic, and political organizational differences among countries, the higher opportunity cost of having children exerted the same impact on the birth rate in all cases.

Opportunity cost is a powerful tool and it will be applied again and again throughout this book. If you integrate this tool into your thought process, it will greatly enhance your ability to understand the real-world behavior of consumers, producers, business owners, political figures, and other decision-makers. Even more important, the concept will also help you make better choices.

Element 1.3: Decisions Are Made at the Margins

If we want to get the most out of our resources, options should be chosen only when the marginal benefits exceed the marginal cost.

If we are going to get the most out of our resources, actions should be undertaken when they generate more benefits than costs, and rejected when they are more costly than the benefits derived. This principle of sound decision-making applies to individuals, businesses, government officials, and society as a whole.

Nearly all choices are made at the margin. That means that they almost always involve additions to (or subtractions from) current conditions, rather than “all-or-nothing” decisions. The word “additional” is a substitute for “marginal.” We might ask, “What is the marginal (or additional) cost of producing or purchasing one more unit?” Marginal decisions may involve large or small changes. The “one more unit” could be a new shirt, a new house, a new factory, or even an expenditure of time, as in the case of a University or College student choosing among various activities. All these decisions are marginal because they involve consideration of additional costs and benefits.

People do not generally have to make “all-or-nothing” decisions, such as choosing between eating or wearing clothes. Instead they compare the marginal benefits (a little more food) with the marginal costs (a little less clothing or a little less of something else). In making decisions individuals don’t compare the total value of food and the total value of clothing, but rather they compare their marginal values. Further, we choose options only when the marginal benefits exceed the marginal costs.

Of course some goods are “lumpy.” It is easy to buy a little more food and a slightly smaller dwelling unit, but hard to add half a child in making fertility decisions. Even in such goods, the marginal principle applies. Parents can invest more or less in child quality (i.e. in investments such as extra tuition, music classes etc. which parents believe will increase a child’s success or happiness in life). Consumers can substitute marginally lower quality cars when auto prices rise (or hold on to their current car longer). The fact that housing often determines the schools that children attend creates an especially problematic issue for families when government policy forces children to go to the school closest to their home rather than offering parents a choice of schools according to the school’s quality and their children’s needs. Things are even less subject to free choice in countries such as China, where residential location (and associated schooling) is highly controlled by the government.

Similarly, a business executive planning to build a new factory will consider whether the marginal benefits of the new factory (for example, additional sales revenues) are greater than the marginal costs (the expense of constructing the new building). If not, the executive and the company are better off without the new factory.

Effective political actions also require marginal decision-making. Consider the political decision of how much effort should go into cleaning up pollution. If asked how much pollution we should allow, many people would respond “none”—in other words, we should reduce pollution to zero. In the voting booth they might vote that way. But marginal thinking reveals that this would be extraordinarily wasteful.

When there is a lot of pollution—so much, say, that we are choking on the air we breathe—the marginal benefit of reducing pollution is quite likely to exceed the marginal cost of the reduction. But as the amount of pollution goes down, so does the marginal benefit—the value of the additional improvement in the air. There is still a benefit to an even cleaner atmosphere (for example, we would be able to see distant mountains or swim in a cleaner river), but this benefit is not nearly as valuable as protecting our lungs. At some point, before all pollution disappeared, the marginal benefit of eliminating more pollution would decline to almost zero.

As pollution is being reduced, the marginal benefit is going down while the marginal cost is going up, and becomes very high before all pollution is eliminated. The marginal cost is the value of other things that have to be sacrificed to reduce pollution a little bit more. Once the marginal cost of a cleaner atmosphere exceeds the marginal benefit, additional pollution reduction would be wasteful. It would simply not be worth the cost.

To continue with the pollution example, consider the following hypothetical situation. Assume that we know that pollution is doing €100 million worth of damage, and only €1 million is being spent to reduce pollution. Given this information, are we doing too little, or too much, to reduce pollution? Most people would say that we are spending too little. This may be correct, but it doesn’t follow from the information given.

The €100 million in damage is total damage, and the €1 million in cost is the total cost of cleanup. To make an informed decision about what to do next, we need to know the marginal benefit of cleanup and the marginal cost of doing so. If spending another €10 on pollution reduction would reduce damage by more than €10, then we should spend more. The marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost. But if an additional €10 spent on antipollution efforts would reduce damages by only one euro, additional antipollution spending would be unwise.

People commonly ignore the implications of marginalism in their comments and votes but seldom in their personal actions. Consider food versus recreation. When viewed as a whole, food is far more valuable than recreation because it allows people to survive. When people are poor and living in impoverished countries, they devote most of their income to securing an adequate diet. They devote little time, if any, to playing golf, water skiing, or other recreational activities.

But as people become wealthier, the opportunity cost of acquiring food declines. Although food remains vital to life, continuing to spend most of their money on food would be foolish. At higher levels of affluence, people find that at the margin—as they make decisions about how to spend each additional euro— food is worth much less than recreation. So as Swedes become wealthier, they spend a smaller portion of their income on food and a larger portion of their income on recreation(5).

The concept of marginalism reveals that it is the marginal costs and marginal benefits that are relevant to sound decision-making. If we want to get the most out of our resources, we must undertake only actions that provide marginal benefits that are equal to, or greater than, marginal costs. Both individuals and nations will be more prosperous when their choices reflect the implications of marginalism.

Element 1.4: Benefits of Trade

Trade promotes economic progress.

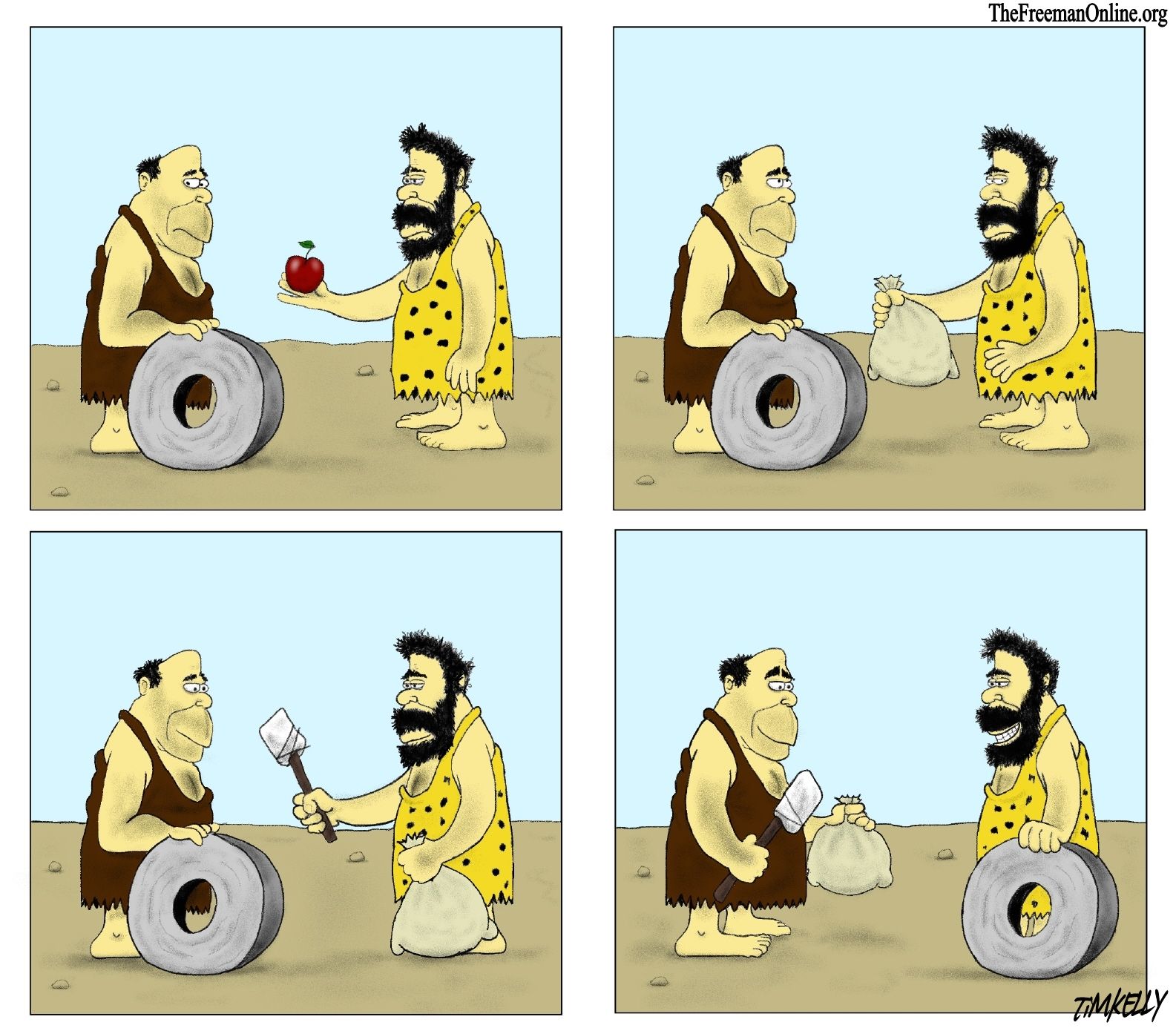

The foundation of trade is mutual gain. People agree to an exchange because they expect it to improve their well-being. The motivation for trade is summed up in the statement: “If you do something good for me, I will do something good for you.” Trade is a win-win transaction. This positive-sum activity permits each of the trading partners to get more of what they value. There are three major sources of gains from trade.

First, trade moves goods from people who value them less to people who value them more. Thus, trade can increase the value of goods even when nothing new is produced. For example, when used goods are sold at flea markets, or through services such as Craigslist (or its local variants such as list.am), the exchanges do not increase the quantity of goods available (as new products do). But the trades move products toward people who value them more. Both the buyer and seller gain, or otherwise the exchange would not occur.

People’s preferences, knowledge, and goals vary widely. A product that is virtually worthless to one person may be a precious gem to another. A highly technical book on electronics may be worth nothing to an art collector but valued at hundreds of dollars by an engineer. Similarly, a painting that an engineer cares little for may be cherished by an art collector. Voluntary exchange that moves the electronics book to the engineer and the painting to the art collector will increase the benefit derived from both goods. The trade will increase the wealth of both people and also their nation. It is not just the amount of goods and services produced in a nation that determines the nation’s wealth, but how those goods and services are allocated.

Second, trade makes larger production and consumption levels possible because it allows each of us to specialize more fully in the things that we do best relative to cost. When people specialize, they can then sell these products to others. Revenues received can be used to purchase items that would be costly to produce themselves. Through these exchanges, people who specialize in this way will produce a larger total quantity of goods and services than would otherwise be possible. Economists refer to this principle as the law of comparative advantage. This law applies to trade among individuals, businesses, regions, and nations.

The law of comparative advantage is just common sense. If someone else is willing to provide you with a product at a lower cost than you can provide it for yourself (keep in mind that all costs are opportunity costs), it makes sense to trade for it. You can then use your time and resources to produce more of the things for which you are a low-cost producer. In other words, produce what you produce best, and trade for the rest. The result is that you and your trading partners will mutually gain from specialization and trade, leading to greater total production and higher incomes. In contrast, trying to produce everything yourself would mean you are using your time and resources to produce many things for which you are a high-cost provider. This would translate into lower production and income.

For example, even though most doctors might be good at record keeping and arranging appointments, it is generally in their interest to hire someone to perform these services. The time doctors use to keep records is time they could have spent seeing patients. Because the time spent with their patients is worth a lot, the opportunity cost of record keeping for doctors will be high. Thus, doctors will almost always find it advantageous to hire someone else to keep and manage their records. Moreover, when the doctor specializes in the provision of physician services and hires someone who has a comparative advantage in record keeping, costs will be lower and joint output larger than would otherwise be achievable.

Third, voluntary exchange allows firms to achieve lower per-unit costs by adopting large-scale production methods. Trade makes it possible for business firms to sell their output over a broad market area so they can plan for large outputs and adopt production processes that take advantage of economies of scale, as happened after 1989 when juices from Moldova entered the global market. Such processes often lead to substantially lower per-unit costs and enormous increases in output per worker. Without trade, these gains could not be achieved. Market forces are continuously reallocating production toward low-cost producers (and away from high-cost ones). As a result, open markets tend to allocate products and resources in ways that maximize the value, amount, and variety of the goods and services that are produced. China is a perfect example of a controlled economy whose citizens, after it joined the global trading system in 1995, were able to take advantage of the signals given by trade and comparative advantage to lift literally billions of people (in both China and other countries in the region) out of poverty.

The importance of trade in our modern world can hardly be exaggerated. Trade makes it possible for most of us to consume a bundle of goods and services far beyond what we would be able to produce for ourselves. Can you imagine the difficulty involved in producing your own housing, clothing, and food, to say nothing of computers, television sets, dishwashers, automobiles, and telephones? People who have these things have them largely because their economies are organized in such a way that individuals can cooperate, specialize, and trade. Countries that impose obstacles to exchange—either domestic or international—reduce the ability of their citizens to achieve gains from trade and to live more prosperous lives. It is true that a dynamic global economy will mean shifts over time in the jobs in any one country. Economists almost universally agree that the proper response is to facilitate workers moving to new jobs rather than shutting off imports.

Element 1.5: Transaction Costs Matter

Transaction costs are an obstacle to trade.

Voluntary exchange promotes cooperation and helps us get more of what we want. However, trade itself is costly. It takes time, effort, and other resources to search out potential trading partners, negotiate trades, and close the sale. Resources spent in this way are called transaction costs, and they are an obstacle to the creation of wealth. They limit both our productive capacity and the realization of gains from mutually advantageous trades.

Transaction costs are sometimes high because of physical obstacles, such as oceans, rivers, and mountains, which make it difficult to get products to customers. Investment in roads and improvements in transportation and communications can reduce these transaction costs. In other instances, transaction costs may be high because of the lack of information. For example, you may want to buy a used copy of the economics book assigned for a class, but you don’t know who has a copy and is willing to sell it at an attractive price. You need to track down someone willing to sell a used copy: the time and energy you spend doing so is part of your transaction costs. In still other cases, transaction costs are high because of regulatory obstacles, such as taxes, licensing requirements, government regulations, price controls, tariffs, or import quotas. Regardless of whether the roadblocks are physical, informational, or political, high transaction costs reduce the potential gains from trade.

People who help others arrange trades and make better choices reduce transaction costs and promote economic progress. Such specialists, sometimes called middlemen, include campus bookstores, real estate agents, stockbrokers, automobile dealers, and a wide variety of merchants. Many believe that middlemen merely increase the price of goods and services without providing benefits. If this were true, people would not use their services. Transaction costs are an obstacle to trade, and middlemen reduce these costs. This is why people value their services.

The grocer, for example, is a middleman. (Of course, today’s giant supermarket reflects the actions of many people, but together their services are those of a middleman.) Think of the time and effort that would be involved in preparing even a single meal if shoppers had to deal directly with farmers when purchasing vegetables, citrus growers when buying fruit, dairy operators if they wanted milk or cheese, and ranchers or fishermen if they wanted to serve beef or fish. Grocers make these contacts for consumers, place the items in a convenient selling location, and maintain reliable inventories. With properly functioning markets, the services of grocers and other middlemen reduce transaction costs significantly, making it easier for potential buyers and sellers to realize gains from trade. These services increase the volume of trade and promote economic progress.

Later, we will discuss how imperfect markets may arise, such as when government or technology gives a monopoly privilege to an individual or firm. The dangers of a single, or monopoly, supplier are especially evident in the case of vital natural resources such as when one country is the only source for another’s natural gas or oil.

In recent years, technology has reduced the transaction costs of numerous exchanges. With just a few swipes on a touch screen, buyers can now acquire information about potential sellers of almost every product. Apps are routinely used to shop for movies, clothing, and household goods, locate a hotel room, obtain tickets for a major concert or big football game, and even hail a taxi. These reductions in transaction costs have increased the volume of trade and enhanced our living standards.

Element 1.6: Prices Create Balance

Prices bring the choices of buyers and sellers into balance.

Market prices will influence the choices of both buyers and sellers. When a rise in the price of a good makes it more expensive for buyers to purchase it, they will normally choose to buy fewer units. Thus, there is a negative relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity demanded. This negative relationship is known as the law of demand.

For sellers, the rise in the price of that product brings extra revenue that makes them willing to supply more of it. Thus, there is a positive relationship between the price of a good and the quantity producers will supply. This positive relationship is known as the law of supply.

The law of demand is so universal that economists have been searching unsuccessfully for decades to find a meaningful exception. However, it is helpful to remember that, while the law of supply is true most of the time, there are exceptions. For example, a college student works (supplying labor) to pay her tuition. Now imagine that her wage (the price of selling her labor) rises. If that enables her to pay for her university costs with fewer hours of work, she might choose to cut back on the amount of labor she supplies so that she has more time to study.

Economists often use graphics to illustrate the relationships among price, quantity demanded, and quantity supplied. When doing so, the price of a good is placed on the vertical y-axis and the quantity per unit of time (for example, a week, a month, or year) on the horizontal x-axis. Using ice cream as an example and the Georgian Lari (GEL) as the currency, Exhibit 2 illustrates the classic demand and supply graphic. The demand curve indicates the various quantities of ice cream consumers will purchase at alternative prices. Note how the demand curve slopes downward to the right, indicating that consumers will purchase more ice cream as its price declines. This is merely a graphic representation of the law of demand.

The supply curve indicates the various quantities of ice cream producers are willing to supply at alternative prices. As Exhibit 2 illustrates, it slopes upward to the right, indicating that producers will be willing to supply larger quantities at higher prices. The supply curve provides a graphic representation of the law of supply.

Exhibit 2: Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium Price

Now for a really important point: The price will tend to move toward a level, GEL 5 per liter of ice cream in our example, that will bring the quantity demanded into equality with the quantity supplied. At the equilibrium price of GEL 5, Georgian consumers will want to purchase 15 thousand liters of ice cream per day, the same quantity that ice cream producers are willing to supply. Price coordinates the choices of both consumers and producers of ice cream and brings them into balance.

If the price is higher than GEL 5—for example, GEL 7.5—producers will want to supply more ice cream than consumers will want to purchase. At the GEL 7.5 price, producers will be unable to sell as many units as they would like. Inventories will rise and this excess supply will lead some producers to cut their price to reduce their excess inventories. The price will tend to decline until the GEL 5 equilibrium price is reached. It is easy to see, then, that if the price is above the equilibrium, market forces will push the price down toward equilibrium.

Correspondingly, if the price of ice cream is less than GEL 5—for example, GEL 2.5—consumers will want to purchase a larger quantity than producers are willing to supply. This generates excess demand and will place upward pressure on price and it will tend to move back toward the equilibrium of GEL 5. The choices of buyers and sellers will be consistent with each other only at the equilibrium price and the market price will gravitate toward this level.

The auction system on eBay illustrates the operation of demand and supply in a setting that is familiar to many. On eBay, sellers enter their reserve prices—the minimum prices they will accept for goods; buyers enter their maximum bids—the maximum prices they are willing to pay. The auction management system will bid on behalf of the buyers in predetermined monetary increments. Bidding ensues until the trading period expires or a person agrees to pay the stated “Buy it Now” price. Exchange occurs only when buyers bid a price greater than the seller’s minimum asking price. But when this happens, an exchange will occur and both the buyer and seller will gain.

Though somewhat less visible than the eBay electronic market, the forces of demand and supply in other markets work similarly. The height of the demand curve indicates the maximum amount the consumer is willing to pay for another unit of the good, while the height of the supply curve shows the minimum price at which producers are willing to supply another unit. As long as the price is between the maximum the consumer is willing to pay and the minimum offer price of a seller, potential gains from trade are present. Moreover, when the equilibrium price is present, all potential gains from exchange will be realized.

Thus, consumers will tend to purchase only units that they value more than the actual price. Similarly, producers will supply only units that can be produced at a cost less than that price. When the equilibrium price is present, units will be produced and purchased as long as the value of the good to consumers exceeds the cost of the resources required for its production. The implication: Market prices not only bring the quantity demanded and quantity supplied into balance, but they also direct producers to supply those goods that consumers value more than their cost of production. This holds true in any market.

Of course, we live in a dynamic world. Through time, changes will occur that will alter the demand and supply of goods and services. Factors such as consumer income, prices of related goods, the expectation of a future price increase, and the number of consumers in the market area will influence the market demand for a good. Changes in any of these factors will alter the amount of a good consumers will want to purchase at alternative prices. Put another way, changes in these factors will cause a change in demand, a shift in the entire demand curve. It is important to distinguish between a change in demand—a shift in the entire demand curve, and a change in quantity demanded—a movement along a demand curve as the result of a change in the price of the good. (Important note to students: Failure to distinguish between a change in demand and a change in quantity demanded is one of the most common errors in all of economics. Moreover, questions on this topic are favorites of many economics instructors. Wise students will take this note seriously.)

Exhibit 3 illustrates the impact of an increase in demand on the market price of a good. Suppose there is an increase in consumers’ income or a rise in the price of frozen yogurt, a common substitute for ice cream. These changes will increase the demand for ice cream at all prices, causing the demand curve to shift to the right from D1 to D2. In turn, the stronger demand will push the equilibrium price of ice cream upward from GEL 5 to GEL 7. At the new higher equilibrium price, the quantity demanded by consumers will once again be brought into balance with the quantity supplied by producers. Note, the increase in demand (shift in the entire demand curve) will result in an increase in the quantity supplied from 15 thousand to 20 thousand, a movement along the existing supply curve.

A reduction in consumer income or lower frozen yogurt prices would exert the opposite impact. These changes would reduce the demand for ice cream (shift the demand curve to the left), lower the price, and reduce the equilibrium quantity exchanged.

Exhibit 3: An Increase in Demand Leads to a Higher Price

Now let’s turn to the supply side of a market. Changes in factors that alter the per-unit cost of supplying a good will cause the entire supply curve to shift. Changes that lower per-unit costs (for example, an improvement in technology or lower prices for the resources used to produce the good) will increase supply, causing the entire supply curve to shift to the right. In contrast, changes that make it more expensive to produce the good such as higher prices for the required ingredients or higher taxes imposed on the producers will reduce supply, causing the supply curve to shift to the left.

Suppose there is a reduction in the prices of cream and milk, ingredients used to produce ice cream. What impact will these resource price reductions have on the supply and market price of ice cream? If your answer is that supply will increase and the market price decline, you are correct. Exhibit 4 illustrates this point within the demand and supply framework. The lower prices of cream and milk will reduce the per-unit cost of producing ice cream, causing the supply curve to shift to the right (from S1 to S2). As a result, the equilibrium price of ice cream will decline from GEL 5 to GEL 3. At the new lower price, the quantity demanded will increase and once again equal the quantity supplied at 20 thousand liters per day. Note: The increase in supply (the shift of the entire curve) lowered the price of ice cream and increased the quantity demanded—a movement along the existing demand curve. If changes occurred that increased the cost of producing ice cream (for example, higher prices for the ingredients), the results would be just the opposite: a decrease in supply (shift to the left), increase in the price of ice cream, and a reduction in the quantity exchanged.

Exhibit 4: An Increase in Supply Leads to a Lower Price

Market adjustments like the ones outlined here will not take place instantaneously. It will take time for both consumers and producers to adjust to the new conditions. In fact, in a dynamic world, the adjustment process is continuous. The impact of changes in demand and supply, and factors that underlie shifts in these curves, are central to the understanding of the market process. Demand and supply analysis will be utilized again and again throughout this book.

Element 1.7: Profits Are a Guide to Productivity

Profits direct businesses toward productive activities that increase the value of resources, while losses direct them away from wasteful activities that reduce resource value.

Businesses purchase natural resources, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial talent. These productive resources are then transformed into goods and services that are sold to consumers. In a market economy, producers will have to bid resources away from their alternative uses because the owners of the resources will supply them only at prices at least equal to what they could earn elsewhere. The producer’s opportunity cost of supplying a good or service will equal the payments required to bid the resources away from their other potential uses.

There is an important difference between the opportunity cost of production and standard accounting measures of cost. Accountants focus on the calculation of the firm’s net income, which is slightly different than economic profit. The net income calculation omits the opportunity cost of assets owned by the firm.

While accountants omit this opportunity cost, economists do not.(6) As a result, the firm’s net income will overstate profit, as measured by the economist. Economists consider the fact that the assets owned by the firm could be used some other way. Unless these opportunity costs are covered, the resources will eventually be used in other ways.

A firm’s profit can be determined in the following manner:

Profit = Total Revenue − Total Cost

The firm’s total revenue is simply the sales price of all goods sold (P) times the quantity (Q) of all goods sold. In order to earn a profit, a firm must generate more revenue from the sale of its product than the opportunity cost of the resources required to make the good. Thus, a firm will earn a profit only if it is able to produce a good or service that consumers value more than the cost of the resources required for their production.

Consumers will not purchase a good unless they value it as much, or more, than the price. If consumers are willing to pay more than the production costs, then the decision by the producer to bid the resources away from their alternative uses will have been a profitable one. Profit is a reward for transforming resources into something of greater value.

Business decision-makers will seek to undertake production of goods and services that will generate profit. However, things do not always turn out as expected. Sometimes business firms are unable to sell their products at prices that will cover their costs. Losses occur when the total revenue from sales is less than the opportunity cost of the resources used to produce a good or service. Losses are a penalty imposed on businesses that produce goods and services that consumers value less than the resources required for their production. The losses indicate that the resources would have been better used producing other things.

Suppose, in Bulgaria (where the currency is the Bulgarian Lev, BGN), it costs a shirt manufacturer BGN 20,000 per month to lease a building, rent the required machines, and purchase the labor, cloth, buttons, and other materials necessary to produce and market one thousand shirts per month. If the manufacturer sells the one thousand shirts for BGN 22 each, he receives BGN 22,000 in monthly revenue, or BGN 2,000 in profit. The shirt manufacturer has created wealth—for himself and for the consumer. By their willingness to pay more than the costs of production, his customers reveal that they value the shirts more than they value the resources required for their production. The manufacturer’s profit is a reward for increasing the value of resources by converting them into the more highly valued product.

On the other hand, if the demand for shirts declines and they can be sold for only BGN 17 each, then the manufacturer will earn BGN 17,000, losing BGN 3,000 a month. This loss occurs because the manufacturer’s actions reduced the value of the resources used. The shirts—the final product—were worth less to consumers than the value of other things that could have been produced with the resources. We are not saying that consumers consciously know that the resources used to make the shirts would have been more valuable if converted into some other product. But their combined choices provide this information to the manufacturer, along with the incentive to take steps to reduce the loss.

In a market economy, losses and business failures work constantly to bring inefficient activities—such as producing shirts that sell for less than their cost—to a halt. Losses and business failures will redirect the resources toward the production of other goods that are valued more highly. Thus, even though business failures are often painful for the owners, investors, and employees involved, there is a positive side: They release resources that can be directed toward wealth-creating projects.

The people of a nation will be better off if their resources—their land, buildings, labor, and entrepreneurial talent—produce valuable goods and services. At any given time a virtually unlimited number of potential investment projects are available to be undertaken. Some of these investments will increase the value of resources by transforming them into goods and services that consumers value highly relative to cost. These will promote economic progress. Other investments will reduce the value of resources and reduce economic progress. If we are going to get the most out of the available resources, projects that increase value must be encouraged, while those that use resources less productively must be discouraged. This is precisely what profits and losses do.

We live in a world of changing tastes and technology, imperfect knowledge, and uncertainty. Business owners cannot be sure what the future market prices will be or what the future costs of production will be. Their decisions are based on expectations. But the reward-penalty structure of a market economy is clear. Entrepreneurs who produce efficiently and who anticipate correctly the goods and services that attract consumers at prices above production cost will prosper. In contrast, business executives who allocate resources inefficiently into areas where demand is weak will be penalized with losses and financial difficulties.

While some criticize the business failures that accompany the market process, this reward-penalty system underlies the prosperity that markets provide. Interestingly, many of the entrepreneurs who initially failed, eventually succeed in a big way. Steve Jobs provides an example. After leaving Apple in 1985, Jobs founded neXT, a firm that he thought would produce the next generation of personal computers. The company struggled. But, Jobs learned from the experience. He returned to Apple in 1997 and soon introduced the iPhone, the iPad, and other innovative products that succeeded spectacularly in the marketplace.

The bottom line is straightforward: Profits direct business investment toward productive projects that promote economic progress, while losses channel resources away from projects that are counterproductive. This is a vitally important function. Economies that fail to perform this function well will almost surely experience stagnation, or worse.

Element 1.8: Incomes Come From Usefulness

People earn income by providing others with things they value.

People differ in many ways—in their productive abilities, preferences, specialized skills, attitudes, and willingness to take risks. These differences influence people’s incomes because they affect the value of the goods and services that individuals are willing and able to provide to others.

In a market economy, most people who earn high incomes do so because they provide others with things they value more than their cost. If these individuals did not provide valuable goods or services, firms (and indirectly consumers) would not pay them so generously. There is a moral here: If you want to earn a high income, you had better figure out how to do something that helps others a great deal. On the other hand, if you are unable or unwilling to help others in ways they value, your income will be low.

This direct link between helping others and receiving income gives each of us a strong incentive to acquire skills, develop talents, and cultivate habits that will help us provide others with valuable goods and services. College students study for long hours, endure stress, and incur the financial cost of schooling in order to become doctors, teachers, accountants, and engineers. Other people acquire training, certification, and experience that will help them become electricians, maintenance workers, or website designers. Still others invest and start businesses. Why do people do these things?

In some cases individuals may be motivated by a strong personal desire to improve the world. However—and this is the key point—even people who don’t care about improving the world, who are motivated mostly by the desire for income, will have a strong incentive to develop skills and take actions that are valuable to others. High earnings come from providing goods and services that others value. People seeking great wealth will have a strong incentive to pay close attention to what others want. And even those people who want to improve the world need information on the education and skills they can acquire, which will do the most to make the world a better place for others. This information is generally provided by the earning opportunities in different occupations.

Some people think that high-income individuals must be exploiting others. But people who earn high incomes in a well-functioning marketplace generally do so by providing others with things they value and for which they are willing to pay. Larry Page and Sergey Brin became billionaires because users found Google better served their needs than Yahoo! or Ask Jeeves. Popular singers provide another example. Beyoncé and Taylor Swift each have huge earnings because millions enjoy their music. The role of a society is to ensure that the “rules” of the game are fair, not to prevent some from winning by a large margin because they are good at the game. Problems arise when early movers lock in technologies that may eventually become outdated but hard to replace. This trade-off leads to a great deal of public policy discussion that is often more a function of political opinion than sound economic analysis.

Business entrepreneurs who succeed in a big way do so by making products that millions of consumers find attractive. The late Sam Walton, who founded Walmart, became one of the richest men in the United States because he figured out how to manage large inventories effectively and sell brand-name merchandise at discount prices to small-town America. Bill Gates and Paul Allen, cofounders of Microsoft, became billionaires by developing a set of products that dramatically improved the efficiency and compatibility of desktop computers. Millions of consumers who never heard of Walton, Gates, or Allen benefited from their talents and products. These men made a lot of money because they helped a lot of people.

Such examples of “good capitalists” can also be found throughout transition economies. Perhaps not as well known as Bill Gates, the Czech Pavel Baudiš built Avast into a major force in cybersecurity and a fortune of many billions of dollars. The Polish mechanic Zbigniew Sosnowski turned a failing state bicycle company into Kross, a major European maker producing over 1 million bicycles a year. Google “Talking Tom Cat” and you will find a very popular set of children’s videos developed by a young Slovenian couple, Izo and Samo Login, and sold to a Chinese buyer for over a billion dollars.

Element 1.9: Value Creates Income and Wealth

Production of goods and services people value, not just jobs, provides the source of high living standards.

Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.

As Adam Smith noted more than 240 years ago, consumption is the objective of all production. But, consumption comes before production only in the dictionary. Income and living standards cannot increase without an increase in the production of goods and services that people value.

Clearly, destroying commonly traded goods that people value will make a society worse off. This proposition is so intuitively obvious that it almost seems silly to highlight it. But policies based on the fallacious idea that destroying goods will benefit society have sometimes been adopted. In 1933, the United States Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) in an effort to reduce supply and thus prevent the prices of agricultural products from falling. Under this New Deal legislation, the federal government paid farmers to plow under portions of their cotton, corn, wheat, and other crops. Potato farmers were paid to spray their potatoes with dye so they would be unfit for human consumption. Healthy cattle, sheep, and pigs were slaughtered and buried in mass graves in order to keep them off the market. Six million baby pigs were killed under the AAA in 1933 alone. The Supreme Court declared the act unconstitutional in 1936, but not before it had kept millions of valuable agricultural products from American consumers. Moreover, under modified forms of the Act, even today the United States government continues to pay various farmers to limit their production. While the political demands of those benefiting from the policies are understandable, such programs destroy valuable resources, making the nation poorer.

The United States is not alone in responding to political pressure to “support” farmers at an enormous cost to taxpayers and consumers. The European Union’s “Common Agricultural Policy” is one of the largest and most controversial parts of the E.U.’s budget.

Farming is not the only industry targeted, either. In the United States, the 2009 “Cash for Clunkers” program provides another example of politicians attempting to promote prosperity by destroying productive assets—used cars in this case. Under the Cash for Clunkers program, car dealers were paid between $3,500 and $4,500 to destroy the older cars that were traded in for a new automobile. Dealers were required to ruin the car engines with a sodium silicate solution, then smash them and send them to the junkyard, assuring that not even the parts would be available for future use. The proponents of this program argued that it would stimulate recovery by inducing people to buy new cars. But the new cars cost more than used ones, and the price of used ones increased because of the decline in supply. As a result, consumers spent more on automobiles (both new and used) and therefore less was available for spending on other items. Thus, the Cash for Clunkers program failed to stimulate total demand. In essence, taxpayers provided $3 billion in subsidies for new car purchases, while destroying approximately 700,000 used cars valued at about $2 billion. Those who could afford new cars were subsidized, while poor people who depend on used cars were punished. And new car sales plunged when the program expired. Germany introduced its own scrappage program, which has been estimated to cost taxpayers over $7 billion, more than twice as much as in the United States.

Similar programs existed in many East European countries, including Russia and Slovakia. In Romania under the program called “Rabla” (the wreck) over 525,000 cars, eight years or more in age, were scrapped for vouchers worth up to €1,500. The program operated between 2005 and 2015, and an individual could turn in up to three older cars for vouchers to be applied towards new cars.

If destroying automobiles is a good idea, why not require owners to destroy their automobile every year? Think of all of the new-car sales this would generate. All of this is unsound economics. You may be able to help specific producers by increasing the scarcity of their products, but you cannot make the general populace better off by destroying marketable goods with consumption value.

A more subtle form of destruction involves government actions that increase the opportunity cost of obtaining various goods. Countries worldwide spend $30 billion a year on fisheries subsidies, 60% of which directly encourages unsustainable, destructive, or even illegal practices. The resulting market distortion is a major factor behind the chronic mismanagement of the world’s fisheries, which the World Bank calculates to have cost the global economy $83 billion in 2012. Furthermore, rich economies (in particular Japan, the United States, France, and Spain), along with China and South Korea, account for 70% of global fisheries subsidies. These transfers leave thousands of fishing-dependent communities struggling to compete with subsidized rivals and threaten the food security of millions of people as industrial fleets from distant lands deplete their oceanic stocks. West Africa, where fishing can be a matter of life and death for the local people, is being particularly hard hit. Since the 1990s, when foreign vessels, primarily from the E.U. and China, began to fish on an industrial scale off its shores, it has become impossible for many local fishers to make a living or feed their families.

Politicians and proponents of government spending projects are fond of boasting about the jobs created by their spending programs and they exaggerate program benefits. This makes economic literacy particularly important. While employment is often used as a means to create wealth, we must remember that it is not simply more jobs that improve our economic well-being but rather jobs that produce goods and services people value. When that elementary fact is forgotten, people are often misled into acceptance of programs that reduce wealth rather than create it.

The focus on artificially creating jobs can be extremely misleading. The great early French economist Frédéric Bastiat clearly pointed out the fallacy in his parable of the broken window from his essay “Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas” (“What is Seen and What is Unseen,” 1850):

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James Goodfellow, when his careless son has happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation—“It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?”Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier’s trade—that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs—I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, “Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.”It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.(7)

Bastiat properly refocuses our attention on wealth rather than production. Creating demand for new production by destroying already existing valuable assets is not an effective way to make a society better off.

Element 1.10: There Are Multiple Sources of Progress

Economic progress comes primarily through trade, investment, better ways of doing things, and sound economic institutions.

On the first day of an introductory economics class, we often inform students that workers in developed countries such as the United States produce and earn approximately thirty times as much per person today as in 1750. Then we solicit their views on the following question: “Why are workers so much more productive today than two and a half centuries ago?” Think for a moment how you would respond to this question.

Invariably, our students mention three things: First, today’s scientific knowledge and technological abilities are far beyond anything imagined in 1750. Second, we have complex machines and factories, far better roads, and extensive systems of communications. Finally, students usually mention that in 1750 individuals and families directly produced most of the items that they consumed, whereas today we typically purchase them from others.

Basically, the students provide the correct explanation even though they have little or no prior knowledge of economics. They recognize the importance of technology, capital (productive assets), and trade. Their response reinforces our view that economics is the “science of common sense.”

We have already highlighted gains from trade and the importance of reducing transaction costs as sources of economic progress. Economic analysis pinpoints three other sources of economic growth: investments in people and productive assets, improvements in technology, and improvements in economic organization.

First, investments in physical capital (such as tools, machines, and buildings) and human capital (education, skills, training, and experience of workers) enhance our ability to produce goods and services. The two kinds of investment are linked. Workers can produce more if they work with more and better machines. A logger can produce more when working with a chainsaw rather than a hand-operated, crosscut blade. Similarly, a transport worker can haul more with a truck than with a mule and wagon.

Second, improvements in technology (the use of brain power to discover new products and less costly methods of production) spur economic progress. Since 1750, the steam engine, followed by the internal combustion engine, electricity, and nuclear power replaced human and animal power as the major source of energy. Automobiles, buses, trains, and airplanes replaced the horse and buggy (and walking) as the chief methods of transportation. Technological improvements continue to change our lifestyles. Consider the impact of personal computers, microwave ovens, cell phones, streaming programs on TV, heart by-pass surgery, hip replacements, automobile air conditioners, and even garage door openers. The introduction and development of these products during the last fifty years have vastly changed the way that we work, play, and entertain ourselves. They have improved our well-being.

Third, improvements in economic organization can promote growth. By economic organization we mean the ways that human activities are organized and the rules under which they operate—factors often taken for granted or overlooked. How easy is it for people to engage in trade or to organize a business? The legal system of a country, to a large extent, determines the level of trade, investment, and economic cooperation undertaken by the residents of a nation. A legal system that protects individuals and their property, enforces contracts fairly, and settles disputes is an essential ingredient for economic progress. Without it, investment will be lacking, trade will be stifled, and the spread of innovative ideas will be impeded. Part 2 of this book will examine in more detail the importance of the legal structure and other elements of economic organization.

Investment and improvements in technology do not just happen. They reflect the actions of entrepreneurs, people who take risks in the hope of profit. No one knows what the next innovative breakthrough will be or just which production techniques will reduce costs. Furthermore, entrepreneurs are often found in unexpected places. Thus, economic progress depends on a system that allows a very diverse set of people to test their ideas to see if they are profitable and, simultaneously, discourages them from squandering resources on unproductive projects.

For this progress to occur, markets must be open so that individuals are free to try their innovative ideas. An entrepreneur with a new product or technology needs to win the support of only enough investors to finance the project. But, competition must be possible to hold entrepreneurs and their investors accountable for the efficient allocation of their resources: Their ideas must face the “reality check” of consumers who will decide whether or not to purchase a product or service at a price above the production cost. In this environment, consumers are the ultimate judge and jury. If they do not value an innovative product or service enough to cover its cost, it will not survive in the marketplace. The proper role of government is to ensure that new and better products have a chance to compete, not to decide which products should be favored.

Element 1.11: The Usefulness of the “Invisible Hand”

The “invisible hand” of market prices directs buyers and sellers toward activities that promote the general welfare.

Every individual is continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command. It is his own advantage, indeed, and not that of the society which he has in view. But the study of his own advantage naturally, or rather necessarily, leads him to prefer that employment which is most advantageous to society. He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was not part of his intention.(8)

Self-interest is a powerful motivator. As Adam Smith noted long ago, when directed by the invisible hand, self-interested individuals will have a strong incentive to undertake actions that promote the general prosperity of a community or nation. The “invisible hand” to which Smith refers is the price system. The individual “intends only his own gain” but he is directed by the invisible hand of market prices to promote the goals of others, leading to greater prosperity.

The principle of the “invisible hand” is difficult for many people to grasp. There is a natural tendency to perceive that orderly outcomes can only be achieved when someone is in charge or through directions from a centralized authority. Yet Adam Smith contended that pursuing one’s own advantage creates an orderly society in which demands are routinely satisfied without centralized planning. This order occurs because market prices coordinate the actions of self-interested individuals when private property and freedom of exchange are present. One statistic—the current market price of a particular good or service—provides buyers and sellers with what they need to bring their actions into harmony with the best possible information on the current actions and preferences of others. Market prices register the choices of millions of consumers, producers, and resource suppliers. They reflect information about consumer preferences, costs, and matters related to timing, location, and circumstances—information that in any large market is well beyond the comprehension of any individual or central-planning authority.

Have you ever wondered why the supermarkets in your community have approximately the right amount of milk, bread, vegetables, and other goods—an amount large enough that the goods are nearly always available but not so large that a lot gets spoiled or wasted? How is it that refrigerators, automobiles, and touch screen tablets, produced at diverse places around the world, are available in your local market in about the quantity that consumers desire? Where is the technical manual for businesses to follow to get this done? Of course, there is no manual. The invisible hand of market prices provides the answer. It directs self-interested individuals into cooperative action and brings their choices into line with each other through price signaling, as described in Element 1.6.

The 1974 Nobel Prize recipient Friedrich Hayek called the market system a “marvel” because just one indicator, the market price of a commodity, spontaneously carries so much information that it guides buyers and sellers to make decisions that help both obtain what they want.(9) The market price of a product reflects thousands, even millions, of decisions made around the world by people who don’t know what the others are doing. For each product or service, the market acts like a giant computer network grinding out an indicator that gives all participants both the information they need, and the incentive to act on it.